In response to a question about the typical work of a Court of Protection judge, the Senior Judge at the Court of Protection (Judge Denzil Lush) has very kindly shared with me some information he has collated about his workload since 2008. He has also permitted me to reproduce a statistical analysis I conducted on it here for others who may be interested in the work of the court to look at.

The statistics relate to applications for permission to the Court of Protection. Except in certain specified circumstances, the Court of Protection requires applicants to seek the Court’s permission before hearing a case. In general, cases requiring applications for permission are not ordinary property and affairs matters, but relate to deputyships and care and welfare issues. Certain groups do not require permission to apply, but in general people who are not deputies or LPA’s will need to seek permission (see the Court of Protection rules for more information on when permission is needed).

Since 2008 Judge Lush has recorded certain details about these applications in a spreadsheet. What follows is taken from the information he has personally recorded, and the outcomes of the applications for permission. Note that the granting of permission does not mean that the court has acceded to applicant’s request, only that the judge has granted them a hearing before the court. The Court of Protection used to operate an alphabetical split on the applications each judge dealt with, so in statistical terms they were likely to represent a fairly randomly selected sample of the types of applications the court receives. However, since taking on more judges last year, the strict alphabetical split has been abandoned. The number of applications for permission heard by the Senior Judge has declined overall (see Figure 1), despite the growing workload of the court overall, because he has picked up other areas of work. And so the fall in applications considered here does not reflect a falling workload of the court – far from it. It should also be noted that the data for 2008 represents only applications made from the month of April, and the data for 2011 stops during September.

As Figure 2 shows, in more recent years more applications have been granted; this may reflect that applications that are being now are more appropriate – and therefore more likely to be granted.

Senior Judge Lush confirms that the majority of these applications are for deputyships, often for property and affairs combined with welfare. The following passages from the most recent Court of Protection report may therefore help make sense of why a relatively high proportion of applications are refused:

'In the 2009 report, we noted that the court was refusing permission in up to 80% of personal welfare applications. In 2010, this figure reduced to around 70%. Permission is most likely to be refused in so called hybrid applications for the appointment of a deputy; that is where the applicant is seeking both personal welfare and property and affairs powers. There are several reasons why the court does not consider it necessary to appoint a deputy to make personal welfare decisions. The main reason is that section 5 of the MCA confers a general authority for someone to make decisions in connection with another’s care or treatment, without formal authorisation, provided: that P lacks capacity in relation to the decision; and it would be in P’s best interests for the act to be done. Another reason is that, when considering the appointment of a deputy, the court is required to apply the principles in section 16(4) that: “(a) a decision of the court is to be preferred to the appointment of a deputy to make a decision; and (b) that the powers of the deputy should be as limited in scope and duration as is practicable in the circumstances.” In reality, a deputy is rarely needed to make a decision relating to health care or personal welfare, because section 5 already gives carers and professionals sufficient scope to act.

The final reason is that personal welfare decisions invariably involve a consensus between individuals connected with P - healthcare professionals, carers, social workers and family - about what decision is in P’s best interests. If the court appoints a personal welfare deputy, particularly if it’s done without a hearing and considering oral arguments from each side, it could upset the balance of that consensus, and could be seen to favour the deputy’s views over others’. '

Senior Judge Lush also cautions that different judges may handle applications for permission differently, and that therefore we should be cautious of extrapolating from the patterns shown here to the wider performance of the court. I have tried to avoid speculation as to why the data shows certain patterns. A fuller analysis would require a careful audit of the paper applications, which I do not have time to do (but which the court itself is not averse to). Perhaps this is a research program for the future. If anyone would like to suggest any reasons for the patterns in the data in the comments, I would be most interests in hearing them. The Court of Protection – and in particular Judge Lush - has been remarkably open and helpful in allowing me to analyse this data and offering their comments on these statistics; a far from the ‘secretive’ court painted in the media.

For the sake of brevity and clarity, the following analysis reflects the data collapsed by year. A summary of the findings is given at the bottom, for those with limited time.

Characteristics of applicants

In the main, the largest number of applications came from family members (631 in total). Of these, the largest subgroup were applications from sons or daughters (including stepchildren, and sons and daughters in law) of P (n=323). A substantial number of applications also came from parents (n=86). There were a few applications from public authorities, mostly composed of local authorities but also some from NHS Trusts. Some legal practitioners had also made applications in their own name.

I explored this data to see whether there were differences in the success rates of different groups of applicants in seeking permission. As Figure 4 shows, although applications from P’s sons and daughters are the most frequently received, these applications are rather unlikely to be granted permission (8%). The most successful applications come from P’s parents (87%), or from public authorities (79%). Applications by siblings, other family members or from friends and neighbours are less successful than those of parents, but still considerably more successful than those of sons or daughters. Applications of legal practitioners in their own name are fairly successful, at 41%.

Legal Representation

I was interested to see whether it made a significant difference to lay applicants (ie. not public authorities or legal practitioners) to have the assistance of a solicitor in drafting their application. Interestingly marginally more applications were granted to those applying for permission without the assistance of a solicitor (76 granted, 75 not), and in fact more applications made with the assistance of a solicitor failed than did not (245 refused, 217 were not).

Interpreting this finding is problematic without more information. It might be tempting to conclude that solicitors’ skills are not needed for an application to the Court of Protection, or that solicitors are generating more work through encouraging unnecessary applications. However, another possibility may that the court is more inclined to hear applications made without the input of a solicitor, in case they conceal issues of pressing importance that are not clearly described in the applications. In research terms, those applicants with and without legal representation are self-selecting groups, and there may be other important differences between the cases they relate to than access to formal legal advice.

Characteristics of P

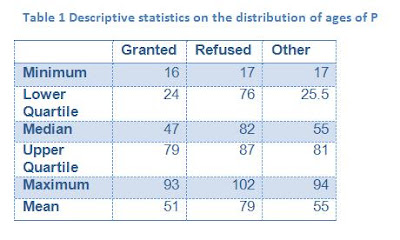

The age of parties whom the applications concern – ‘P’ – ranges from 3 to 102 years old. There were two cases where applications were made in respect of people under the age of the court’s jurisdiction (16, see MCA s2(5)) – and disappointingly enough, one of these was made with the assistance of a solicitor. Despite the potentially wide range of the court’s jurisdiction, the median age of P was 80 years old and the mean was 70. The distribution is negatively skewed, that is to say - the majority of subjects of applications were clustered towards the older end of the range. Table 1 (below) gives descriptive statistics about the ages of the parties whom the applications concerned.

Figure 6 breaks down applications by the gender of P. The chart shows that the great majority of applications concerned women. Furthermore, a far greater proportion of applications relating to women were refused compared to those relating to men.

I speculated that this may be because of women’s longevity over men, and because applications relating to older people were in general less likely to be granted. These two histograms in Figure 7 break down the age distribution by gender and by whether or not an application was granted or refused.

For women, it would seem, the overall number of applications granted is fairly evenly distributed over the lifecourse, and many applications relating to older women are refused. Many applications relating to older men are also refused, but there is a particular spike in applications granted that relate to younger men. So a large number of applications concerning older men and women are rejected, but the court tends to receive and hear a large number of applications about younger men.

Figure 8 shows the number of applications the judge received as a function of P’s diagnosis (as recorded by Judge Lush, but collapsed into fewer categories by me). The vast majority (61%) of applications relate to people with dementia, including 28% of all applications that specified Alzheimer’s disease and 23% that specified vascular dementia. Developmental disabilities also make up a large proportion, including “learning disability” (8% of all applications); autism (5% of all applications); cerebral palsy (2% of all applications); or other developmental conditions – including chromosomal disorders (1% of all applications). Applications relating to adults with acquired brain damage of cardiovascular origin (e.g. stroke, haemorrhage etc) were also a substantial group, and applications relating to adults with progressive neurololgical conditions like MS or Parkinson’s were a substantial minority. Surprisingly few applications relate to people with mental illnesses like bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorders. And the number of applications concerning people with significant disorders of consciousness like coma or PVS were very few indeed.

It is possible that the differences in the success of applications relating to men and women (see Figures 6 and 7 above) may be explained by reference to gender differences in their diagnoses. The histogram in Figure 10 shows that whereas women make up a disproportionate number of applications relating to people with dementia (which are less likely to be granted). In contrast, the numbers of men and women with developmental disabilities or acquired brain damage (which are more likely to be granted) are more evenly distributed. In the wider population, men are more likely to be at risk of certain developmental disorders like autism than women are.

Discussion

These data help to build up a picture of the kinds of applications being made to the Court of Protection. They suggest that the vast majority of the applications received by the court are from the children of older parents, usually with dementia. However, these kinds of applications are more likely to be refused permission than granted, perhaps for the reasons given in the Court of Protection report quoted above. A large minority of applications come from parents or other relatives of younger people with developmental disabilities, and these applications are much more likely to be granted. Another significant group of applications relate to younger adults with an acquired disability; the probability of such an application being granted being around one-third.

It would be interesting to explore why the court receives such a large number of applications from the sons and daughters of older adults, and why these are less likely to be granted than applications from parents of younger people with developmental disabilities. Without a proper audit of the paperwork, it would be dangerous to speculate on why this may be the case, and so this may be a project for the future. Furthermore, as noted by the judge, these patterns may not be reflected by the work of the court as a whole as judicial practices may vary. Your thoughts on this, however, are very welcome in the comments below.

The role of adult children, in respect to a dementing parent, is increasingly held in suspicion by health and social services due to the 'elder abuse'lobby and judgements of social workers. This is now probably part of the court's own conciousness too.

ReplyDeleteThis default position is so unlike that of family orientated and accepting countries that we now have old people being abused by the very agencies who are supposed to care. Adult children lack credibility in the system now to complain thanks to the development of a safeguarding industry led by prescriptive, life inexperienced, social workers and their rigid management. If you are an adult child of an incapacitated parent the chances of not being in dispute with social services over their care is low, hence the successful use by LA's of COP to oust adult children or separate from parent.

Be fearful of growing old in the UK- no one cares. Your children if not judged perfect by a social worker will not be allowed to care or fight on your behalf.

The MCA /Court of Protection gives too much weight to the undefined vague notion of best interests. Those who themselves would in all likelihood object to being treated within this regime if in P's place have no problem deciding for P in the COP setting or in the social services world. The scenario in a local authority that I have personally experienced is farcial: the social worker enters the room, looks at the client and loudly pronounces she is acting in the client's best interests; yet she has no evidence that the client lacks mental capacity! This term is so frequently bandied about by health and social care professionals that it is no more than power arrogance in the face of ignorance.

No one has the time to get to know elder person P well and the family are frequently in dispute so sidelined.

Most of us want to live like others we see or know. Being mentally incapacitated, especially if one looses capacity in adulthood / old age does not fundamentally change this. To have strangers who decide you should be protected when you yourself took huge risks would be painful to most. Protection and care should not mean denial of your person, which is patronising. Care should support who we are, we only have one life and risk can never be completely removed from our lives. This is fundamentally what being human is about and related to human rights which the current system can easily flout because of the control exerted by 'pseudo professionals'.

We need to recognise where people have come from to recognise what they are being denied.

The MCA has become unbalanced in the way it is operated and is a threat to all of us if some of its tenets are not seriously questioned. This issue will gain hold as has the notion of the 'secret courts' with the public. Increasingly growing numbers of the public are questioning whether social services are truly acting in their clients best interests.

Hi Anonymous,

ReplyDeleteThanks for your comments. Although these data do suggest that the CoP is more reluctant to grant deputyships to adult children of older parents, I think it's really difficult to tell from the data alone the reasons for this. It would be great to carry out a more detailed analysis of the paper trail, which unfortunately I don't have time to do at present.

There are many tensions underpinning the MCA, and as you say the concept of best interests is rather ill defined, and hence there is a risk of arbitrariness in outcomes under the MCA. However, once we've accepted having a substitute decision-making mechanism, it becomes very difficult to balance flexibility to cover all kinds of decisions, without introducing potential arbitrariness. Ideally, Court of Protection case law would over time provide a more consistent, detailed and nuanced approach that would reduce the risk of arbitrariness, but because so little case law is published, because the cases are highly "fact specific" (and in the case of DOLS, not at all consistent), this isn't happening as much as we might hope.

However, your comments are pointing to a more fundamental issue than the legal principles of capacity and best interests; and that is the question of "who decides". As a very flexible legal device, the MCA empowers a range of people to make decisions (unless there is a valid LPA/deputyship). Often these are professionals, and sometimes carers. Anyone who works in community care knows that relationships between professionals and carers can be a tinderbox, and so it's not suprising the MCA is a flashpoint for tensions between carers and professionals. Or - more widely - between the family and the state (as most health and social care professionals in the UK are working for the state). This taps into some very fundamental political issues, and is - I believe - rather predictably reflected in the attitude to the MCA and the Court of Protection of anti-state papers like the Mail. While I do share some of their concerns (the Neary case is a good example of how wrong substitute decision-making can go), I think these papers tend to neglect the pro-family line the Court of Protection typically takes, and also the reality that there are fairly high levels of abuse - financial and neglect - of family members by their relations.

I don't think there's an easy answer to this. The arguments you raise aren't so much about empowering the individual to make decisions (which is the argument of the disability rights lobby), but empowering the family against the state, which raises slightly different issues. Having seen first-hand plenty of neglect and financial abuse of older people by their adult children when I worked in care, I would be very reluctant indeed to empower them through deputyships without further monitoring. One crucial difference between older adults and young adults with learning disabilities is the issue of inheritances. At the same time, I have concerns that the MCA runs the risk of sidelining the majority of carers - who usually are non-abusive, caring and a rich source of knowledge about a person. I'm not sure the MCA is sensitive enough to issues around continuity of care for professionals who - as you say - often treat their qualifications as a substitute for getting to know a person over time. Other countries have systems where it is easier for people to appoint their own deputies, even if by MCA standards they "lack capacity". However, I've had trouble finding out how these are managing abuse risks. When I've found out a bit more, I'll post on this, and the family-state tensions issue that you raise.

Dear Lucy

ReplyDeleteYou have just re-iterated the 'abuse lobby's' objections to family / adult children's roles. Yes abuse and neglect exist in families. But in the position of P I would accept my family in difficulty doing this than the paid 'professionals' and public / private institutions, who we daily see have widespread abuse and neglect within them. They actually do this with impunity without heavy handed safeguarding to immediately act. Greater levels of neglect in 'care settings' and by formal carers go hidden because whistleblowing is not rife and is dangerous to 'jobsworths'. This far outstrips family neglect if one were to really study this seriously, (or allowed to by government DoH- not in their best interests).

I do not personally know of anyone who has had a loved one in a nursing / care home situation who has not been neglected to some degree in terms of the care given. That those with dementia or elders in general rarely complain is from fear of those in power to whom they must sucumb to meet very basic needs for services- hidden in care homes they are not even seen or heard by neighbours.

I think public debate is needed on the MCA / COP because the whole area is contentious and driven by 'vested interests'.

Financial abuse is more difficult, because most of us would not object to leaving wealth to our children- this is now a political issue here.

So if our relatives need money we may not when capacitated have refuse this ourselves, even to the point of denying ourselves what we need (not uncommon in elders of the old generation or some newer elders).

Families are complex and there may well have been a flexible financial helping arrangement within a family when needs arose. When the person becomes incapacitated this may not be understood / recognised or the 'best interests' of P really accepted as part of what has long been 'normal'. These are areas where public discussion with elders themselves is missing. That is the problem with COP development, it has been developed top down, without input of those who may one day be P.

Just to follow on

ReplyDeleteI do support empowering people to make their decisions, but the unnecessarily complex assessment of capacity to determine that a professional can assess capacity in a formally prescribed manner is a deterrent to empowerment.

In stroke victims who loose linguistic skills. hear and see poorly and cannot use alternative methods e.g. written to convey their responses may be wrongly judged as indicating lack of capacity because the work needed to get a clear consistent view needs so much ongoing time and skills that this is deemed unrealistic.

An example from experience is someone with cognitive impairments with poor hearing and often pre-occupied with own concerns when questioned, so not attentive. The answers given in a single capacity assessment prove to deem P inacapable. Yet when assessed on another occasion P fits the criteria for having capacity for the same decision. It is luck that this assessment was conducted more than once.

The whole issue of capacity assessments is a minefield working against empowerment. I think the countries (most =in the world) that allow those 'without capacity' to appoint deputies is highly empowering and says a lot. Perhaps these do not assume abuse unless proven fact- the exact opposite to the UK scenario since safeguarding took hold. Life is based on trust, but the UK oppressive laws are not.

Hi Anonymous,

ReplyDeleteWith respect, I don't think I've said I object to family roles, just that I feel there does need to be a monitoring framework - just as there does for professionals. My interest in the MCA is around empowering P; often that can be achieved through empowering P's family, but not always.

You write: "Yes abuse and neglect exist in families. But in the position of P I would accept my family in difficulty doing this than the paid 'professionals' and public / private institutions, who we daily see have widespread abuse and neglect within them". It is true that carers who are undersupported and at the end of their tether are sometimes labelled abusive. I think the issue of lack of support for carers is really not adequately appreciated by some professionals, and not adequately remedied in our rather weak carer's legislation. It is unhelpful to apply the same label of 'abusive' to a tired carer who snaps or is abrupt, with, say, the family of Margaret Panting. But it does have to be acknowledged that aside from issues around support for carers, really serious family abuse and neglect does exist. That's why I say, a mechanism that merely empowers family with no monitoring framework would be very problematic. I would also add that abuse in institutions is much more likely to be in the public eye than in family settings, because unless the abuse victim is actually killed, or criminal charges are brought, the victim and family are generally owed a duty of confidentiality by the safeguarding authorities. The same cannot be said of formal care providers.

On the issue of 'financial abuse', you write: "most of us would not object to leaving wealth to our children... So if our relatives need money we may not when capacitated have refuse this ourselves, even to the point of denying ourselves what we need". I think you may raise a valid point that the MCA can create problems for 'gifting'. This may very well need addressing and further public debate. But again, I would caution that there really are cases where there is a serious conflict of interest between P and P's family around how money is spent. When I worked in care there were cases where a wealthy person's adult children, who controlled their assets, would refuse to pay for more support for their care needs. I'm not talking about 'going without' for luxuries, but for basic things like being washed and fed and helped to the bathroom. On occasion I saw levels of neglect among wealthy people whose children controlled their assets that was far, far higher than among those supported by the local authority. Other issues arise around the sale of the parental home when a person moves into residential care. There have been cases where family have resisted such a move because they saw the loss of their inheritance or even their own home. These issues may be addressed by the Dilnot recommendations, but it's looking increasingly unlikely. In the meantime it is worth noting that such financial conflicts have had very adverse outcomes for the older person. See, for instance, this case:

http://www.thisiscornwall.co.uk/Death-sparks-questions-care-elderly/story-11445581-detail/story.html

I do not suggest for one second that the majority of families are like this, but neverthless these cases do occur, and also need to be taken into consideration by the law.

Dear Lucy

ReplyDeleteYour examples reflect the extreme end of a spectrum of possible financial involvement with the assets of P by P's family / children which could be deemed criminal in law- there can be no excuse for this behaviour. It is true that the first call on P's assets should be for P's welfare needs. But what if when P was capacitated and needing help this was not taken up because of P's own reluctance to spend the money? After loosing capacity P's family knowing this will be expected to spend it on P's behalf. Some will be relieved to be able to do what P refused to do when told to do so by them.

I do not accept that most abuse in institutions will be in the public eye- Winterbourne took a long time to get noticed and only because of a persistent whistleblower. Even the Neary case could have gone differently had not Neary gone public. Most neglect / abuse, including of power, in/ by institutions is 'drip drip' and invisible so we repeatedly hear year after year of the same problems in more locations. Home care is increasingly the abuse situation as private agencies send strangers with no care experience into homes of the most vulnerable.

As to safeguarding - a referral of a 'false accusation' of abuse / potential to abuse by a carer to the police creates a permanent record and potential CRB situation where livelihoods are destroyed- there has been a spate of concerns around this. For a carer on whom P may initially depend and who later needs to work this may well be disastrous.

I am a lot older than you with decades of experience in the health / social care field as a professional. Nothing has changed over many decades for the most vulnerable in society, except media attention and more legislation to either control them or protect them. It is society that needs to change- not laws.

Hi Anonymous,

ReplyDeleteTo be honest I'm in two minds about responding again, as your comments are starting to take a somewhat personal tone, and I feel that you're reading more into what I've written than what I've said.

On 'extreme' financial abuse, some instances will be criminal - but many are not, and there needs to be an appropriate forum for dealing with all shades of these issues. This applies as much to formal care providers as to families. The example of financial conflicts of interest where family haven't purchased care services because they want to preserve their inheritance are not criminal issues, and the CoP is currently the only appropriate forum for them to be dealt with.

I haven't ever said "that most abuse in institutions will be in the public eye"; I completely agree with you that most abuse is unseen and unreported. Regulatory and whistleblower approaches are currently failing. Even where abuse is uncovered, often it still is not reported in the media. My point was merely that family abuse is even more likely to be to go unreported, because of confidentiality duties of safeguarding teams. If you look through my blog I'm often critical of 'safeguarding' practices by social services, and have expressed concerns about families being sidelined. I've also often written about the widespread risks of institutional abuse.

It is true that the examples I gave are at the extreme end of the spectrum, but the law has to cater for its full breadth. My point is merely that these extremes do exist, and aren't a fantasy of some 'abuse lobby'. I don't think it's acceptable for lawmakers to ignore these extremes and regard them as 'collateral damage' of the state stepping back from a safeguarding role.