Human rights organisations are rightly concerned about the civil liberties of protestors and those subject to control orders. Charities who promote the rights of disabled and older people are rightly concerned about their wellbeing in care services. But I'm troubled that few of these organisations seem to be kicking up a fuss about the liberty rights of adults in care services. Unlawful deprivation of liberty is an abuse in itself and a risk factor for situations like Winterbourne View. I'd like to call upon NGO's working to promote the human rights of older and disabled people to take a stand on the DoLS - people in care services have liberty rights, just like anybody else.Like liberty itself, deprivation of liberty comes in all kinds of shapes and sizes. There's the paradigm case of the prisoner, which we easily call to mind when we think of detention, and perhaps also certain forms of psychiatric detention. Then there are various 'borderline cases', which the courts have (broadly) held do not amount to detention, and yet many campaigners feel that they do - like control orders placed on terror suspects, kettling of protestors, and so on. In the human rights community there has been considerable focus on these particular borderline cases - but in my small corner of research I worry about another community, much larger than that affected directly by control orders, and affected for far longer than kettled protestors, that human rights groups have barely spoken about. There are many thousands of adults with mental disabilities, with conditions like dementia, who live under regimes easily as restrictive as control orders, many of whom who have no safeguards at all, or extremely weak safeguards. Occasionally these cases are so extreme - like Winterbourne View - they hit the headlines, and occasionally cases that might be more typical - like that of Steven Neary - spark interest in the media. But somehow these fall into a separate bracket than other liberty issues, they do not seem to spark the same concerns about the liberty rights of our fellow citizens and what their implications are for a democratic society. They continue to be talked about in social care circles, but in human rights circles they seem to have sunk without a trace.

I have enormous respect for human rights NGOs like Liberty and Justice. I am a paid up member of Liberty, and have been for years. I am a member of Justice's student human rights network. I have enormous respect for the other organisations I am about to talk about, which work in the field of disability rights or rights of older people. But for quite some time now I've been wondering - why are none of these NGO's with a high profile on liberty issues, on disability rights issues, talking seriously about liberty rights in care? Why are none of them kicking up an enormous stink about the catastrophe that is the deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS)? In fairness, and as I'll show in a bit below, some are making a few noises about the DOLS, but in comparison with other campaigns and rights-issues these groups campaign on, DoLS really just fade into the background. Yet anybody who is serious about liberty rights should be really concerned about DoLS.

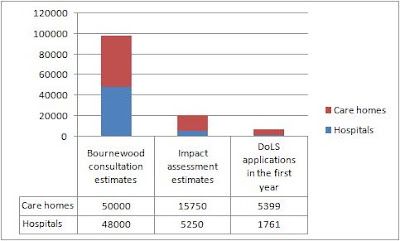

There are many tens of thousands of older people and people with dementia, with learning disabilities and other mental disorders who are subject to such severe restrictions on their liberty they mirror control orders, and will often constitute a deprivation of liberty. We know that a few thousand of these have the benefit of the DoLS, but it seems very likely that many are detained with no safeguards at all. The chart below shows early estimates, just after the ruling in HL v UK (2004) of how many people could require Article 5 safeguards in care homes and hospitals, it shows the estimate from the rather conservative impact assessment for the DoLS, and then it shows how many DoLS authorisations were issued in the first year. The numbers are rising, but very slowly, but note that the estimates on the chart count people whereas the DoLS data counts authorisations - and any individual may have multiple authorisations in a year. In short - it looks as if lots of people have slipped through the net.

The CQC have also said in the first and second reports on the DoLS, and in their Mental Health Act (MHA) visiting reports, that they have come across many examples of unlawful deprivation of liberty. Imagine if Her Majesty's Prison Inspectorate routinely found prisoners who hadn't been arrested or brought to court, imagine if the prisons had just banged them up without any authority. I think it would merit more than a a few comments in a report that only people working in the prison system read, it would be a national scandal. It seems possible that there are many thousands of people in care homes and hospitals today who are unlawfully deprived of their liberty. Imagine if thousands of people were subject to control orders, perhaps even tens of thousands - everybody would be talking about it. But on DoLS - virtual silence.

Furthermore, it seems likely to me and others that the DoLS are 'not fit for purpose', that even where the DoLS are applied they do not provide an Article 5 compliant legal framework for detention. There's the problems with the appeal process, perhaps best exemplified by the fact it took Steven Neary's father a year to get his son home from being unlawfully detained in a care home (here are some reasons why). Contrast this with the six months it took HL's carers to get him home using habeas corpus and consider - who, in public life, is asking whether this new framework that is meant to prevent Bournewood scenarios is functioning properly? Ponder this too: because no data is collected on the outcome of the appeals process, for all we know the DoLS have only ever released one person from detention (Steven Neary). One person. And nobody seems to be asking any questions about that. And what about the care services who have unlawfully detained people - have any of them been directly litigated? Is there actually any realistic source of pressure to comply with the DoLS?

And then there's the state of case law on the meaning of deprivation of liberty - who is speaking out about that? There's the Cheshire judgment, which finds that if somebody is subject to equivalent restrictions on their liberty to 'an adult of similar age with the same capabilities and affected by the same condition or suffering the same inherent mental and physical disabilities and limitations', then they are probably not deprived of their liberty. Imagine if we said of dangerous criminals that if they were held in circumstances comparable to other dangerous criminals they were not deprived of their liberty? Several eminent mental health and human rights lawyers have questioned whether the 'comparator' approach effectively discriminates against disabled people by setting the threshold of restrictions much higher for them before they are entitled to safeguards. But where are the disability rights organisations speaking out about this ruling? Several lawyers have also questioned whether Cheshire makes a nonsense of the DoLS, and perhaps even the Mental Health Act itself, because it is hard to say when a person could be said to be detained under those Acts. Or try this one for size - in C v Blackburn and Darwen Borough Council [2011] a man with learning disabilities was confined to a care home he did not want to live in, when he left the care home he had to be escorted at all times by staff, he had even hammered the door down trying to escape - but a court found that he was not deprived of his liberty. I find this judgment absolutely staggering, and I doubt many people in human rights circles would feel comfortable with it, or what its implications might be. Yet despite a few bloggers and lawyers writing in blogs and journals read by bloggers and lawyers, who is talking about it? Nobody. I'll say again, if these judgments were affecting any other group, I think there would be a national outcry.

To confirm my suspicion that nobody is really talking about DoLS, I did a bit of research using a very crude content analysis method. Basically, I did site searches on Google for various NGOs and Quangos to see how often their websites were using key terms which could indicate an interest in these liberty issues and DoLS. I put this in a google spreadsheet so you can look at the figures yourself. The results, to my mind, were quite interesting.

Let's start with mentions of the DoLS in contrast with mentions of other liberty limiting regimes like 'control orders' and the

Mental Health Act (MHA). For Liberty and Justice, there were 321 and 91 mentions of control orders, respectively, but literally not a single mention of 'deprivation of liberty safeguards' on their websites. They did mention the MHA a handful of times, indicating they are aware of and interested in liberty issues relating to mental health, but nothing like on the scale of control orders. The EHRC mentions DoLS 20 times on its website, which is good and they have done some great interventions in DoLS cases in court, but contrast this with 160 hits for the MHA and 24 hits for control orders. The CQC, as you'd hope, have hundreds of thousands of hits for DoLS on their website, as well as the MHA (unsurprisingly, no mention of control orders). But what about the NGO's involved in disability rights?

So, the disability NGOs are talking about DoLS more than the human rights NGOs, but not nearly as much as the MHA, and not as much as you might hope if potentially thousands of people with dementia, learning disabilities and other mental disorders are being unlawfully detained.

hits for DoLS hits for MHA Mencap 16 6 BILD 9 46 Alzheimer's Society 3 3 Dementia UK 3 6 Age UK 70 56 Mind 53 534 Disability Rights UK 0 6

It's not that these disability NGOs aren't talking about rights though. Most of them use the word 'rights' on their websites many hundreds, if not thousands of times. But they seem to be talking about different kinds of rights to liberty rights. I did a set of searches contrasting mentions of various 'rights' buzzwords: freedom, choice, liberty, dignity, detention, and plotted the results (as proportions, so usage of a word on a given website is compared against other words on that site - not other sites - as sites varied in size):

So the disability-oriented NGOs use the words 'choice' and 'dignity' far more than they use the word 'liberty', or words relating to liberty - like freedom or detention (nb: many mentions of 'freedom' turned out to relate to Freedom of Information, or bus passes). I've long felt that many organisations associated with disability and care issues are more comfortable with 'dignity' than 'liberty' rights. "Choice" is also a favoured word in social care circles, but - to my mind - it offers a rather weak form of liberty, as the 'choices' on offer still remain within the control of whoever is offering them. Choice can be very important, but although it is very central to market-thinking about care provision, choice is not liberty.

Contrast this with the pattern of buzzword use on human rights NGO's websites:

Immediately you can see that they're not so concerned with 'choice' or 'dignity', but liberty, freedom and detention feature highly (you would expect Liberty to talk about liberty a lot, but note that Justice does as well). So human rights NGOs seem to be much more oriented towards liberty rights than dignity rights, especially in comparison with disability NGOs. And finally, the CQC and the EHRC:

Both organisations mention detention a handful of times, although not as much as the human rights NGOs. But CQC places a lot more emphasis on dignity and choice and EHRC placing much more emphasis on freedom. If you see EHRC as being more of a 'human rights' organisation, and CQC as more of a disability/care oriented organisation, then that fits the pattern just described for the NGOs.

This content analysis is far from perfect - it relies upon a Google site search, it counts hits not usage of particular words, it ignores context, and also its slightly confounded by things like freedom bus passes. But I think it does suggest that although 'rights' discourses are pretty pervasive throughout these NGOs and Quangos, the kinds of rights different organisations and NGOs are interested in differ markedly. NGOs oriented towards civil rights and freedoms, in line with a more traditional liberty-oriented conception of human rights, are very deeply concerned with detention. But given their silence on DoLS, it would seem they are only interested in particular forms of detention - the unlawful detention of older people and people with disabilities seems to have passed them by. Meanwhile, the organisations who are intimately involved with working with people with dementia and learning disabilities, who conduct many important and laudable campaigns to improve conditions in care settings and life opportunities, seem to connect these issues far more with 'dignity' and 'choice', rather than liberty. Put bluntly, those oriented towards care don't care much about liberty; those oriented towards liberty don't care much about care. As a result, nobody who you might expect to give a damn about the problems with DoLS is really rocking the boat.

Its not that dignity rights have no value - cases like Price v UK and Bernard v London Borough of Enfield show that it can be very usefully deployed. But we should also bear in mind that in legal terms, dignity offers relatively weak protection, it certainly doesn't carry with it the well established case law, and procedural safeguards of Article 5. And dignity can also be deployed in ways that might be quite antithetical to liberty and self-determination. Elaine McDonald was told by the court that to use incontinence pads when continent was 'dignified', although she didn't experience it that way. In C v A Local Authority the staff's idea of 'dignity' was used to justify seclusion of a young man with learning disabilities in conditions which most of us would consider undignified to say the least. Cases like C v A Local Authority also show that dignity can be enhanced when liberty issues are taken seriously, because it requires independent scrutiny of restrictive practices. It will be interesting to see, when the Serious Case Review is published, whether the victims of abuse at Winterbourne View were subject to frameworks like DoLS which inject external scrutiny to the conditions of detention, and offer families opportunities to speak out about their concerns. My money is that they weren't, and I don't understand why so few organisations (rightly) shouting about Winterbourne View aren't raising this question. The question we've settled for is "where was the CQC?", forgetting "where were the best interests assessors, mental capacity assessors, Independent Mental Capacity Advocates and rights of appeal to the Court of Protection?" If detention under DoLS should be in a person's best interests, and if they should be supported and enabled to appeal against detention, why on earth weren't Winterbourne View patients all in the Court of Protection? Something has gone horribly wrong here, and voluntary and unenforceable dignity codes aren't going to fix it.

Neither does there seem to be any necessary reason why organisations that are (rightly) worried about control orders are not equally worried about the liberty rights of disabled and older adults subject to similarly restrictive regimes in care settings. Liberty says 'We seek to protect civil liberties and promote human rights for everyone', and Justice says 'We promote access to justice, human rights and the rule of law'. On paper, therefore, they should be worried about DoLS.

We might speculate on all kinds of reasons why this could be the case. We might speculate that DoLS are too new, too complicated, and its too weird to think about detention in community settings. But none of these factors stop people worrying about control orders. Perhaps I'm being too cynical - I hope I am - but I do wonder if lurking in the back of our minds is a nasty, dangerous, belief: that people in need of care don't need liberty. That we'll offer them dignity and choice (safe choices) instead, we'll keep them safe and warm and make sure they don't get into trouble. That seems to be the line of thought that connects Cheshire to this near-silence on liberty rights in care. Because the trouble with liberty is it carries risks, risks that we are often unquestioningly drawn to mitigate, perhaps particularly for those involved in caregiving. Thinking about liberty issues subverts the holdy-handsy image of care on the brochures of the care services our loved ones, our fellow citizens, use.

But think about this. Arbitrary and unscrutinised deprivation of liberty is an abuse in itself, and it carries risks of further abuses. It carries the risks you might expect from unscrutinised and unchecked power over the powerless, creating situations like Winterbourne View. It adds to risks of inappropriate and excessive use of restraint and sedation. It carries risks of severing people from their loved ones, their homes and communities, with few accessible checks and balances. Over a lifetime it also carries risks of smothering individuality and potential for flourishing, it dominates a population whose rights to self-determination can be systematically denied and drilled out of them. I can't help but feel that if this were any other population, more people would be talking about this.

At first I wondered if this liberty-blindness stemmed from the wider social invisibility of the population affected, but actually, the more I think about it, the more I think that's not it at all. Almost all of us at some point in our lives will care about somebody who develops dementia, or has a brain injury, or has a learning disability or mental illness. Many of us will eventually develop these conditions ourselves. The organisations I'm talking about do a lot of awareness raising around the problems these populations face. I'm not sure the problem lies in invisibility - I think liberty issues around care may be all too visible. They are visible there in that nice care home we placed our loved ones in, with the baffle locks on the doors. They are visible when we worry and fret about how we will move a relative into a nice safe care home against their wishes, because of the risks of remaining at home. They are visible there in that nice supported living service where everybody learns life skills and goes bowling, but never has sex, or gets drunk, or goes for a walk without telling anybody. And they're there when things turn darker, and they can't leave. It's not that liberty issues in care aren't visible, it's that we really don't want to look.